Introduction to Brook Trout

The brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) is a beautiful and iconic freshwater fish native to eastern North America, in the United States and Canada. Known by various names—such as eastern brook trout, brook char, speckled trout, brookie, and squaretail—this fish is a favorite among anglers and nature enthusiasts.

Interestingly, the name “brook trout” is a bit misleading. These fish belong to the Char genus (Salvelinus), not the true trout genus (Oncorhynchus). This means they’re more closely related to other char species like lake trout, bull trout, Dolly Varden, and Arctic char than to actual trout. Both char and trout are subgroups within the salmon family (Salmonidae).

Brook trout thrive in clean, cold water. When water temperatures or in-stream sedimentation increases, brook trout tend to disappear from the picture; therefore, they’re considered an indicator species, like the proverbial “canary in a coal mine.” Wild brook trout populations indicate the water quality and overall health of the aquatic environment that they live in.

Brook trout is the state fish of Michigan, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Vermont, Virginia, and West Virginia. It’s also the provincial fish of Nova Scotia. Source

What Do Brook Trout Look Like?

Brook trout are stunning fish with unique and vibrant features that set them apart from other species. Here’s how to recognize one:

- Color Patterns: Like other char fish, brook trout have light spots on a dark background, unlike true trout, which have dark spots on a light background.

- Vermiculations: Their olive-green backs, dorsal fins, and tail fins are adorned with swirling yellow lines in a wormlike pattern called vermiculations.

- Side Markings: Their sides are olive to dark green, decorated with round yellow spots and striking red spots ringed with blue.

- Belly and Fins:

- The belly is white with orange or red hues, becoming a vibrant orange-red during spawning season.

- The lower fins (pectoral, pelvic, and anal) are red with a thin black streak on the edge, bordered by a thicker white stripe.

- Tail Features: Their tails have a slight fork and are olive-green with a subtle pink tint, earning them the nickname “squaretail.”

- Mouth: Brook trout have a notably large mouth that extends beyond their eyes, a key identifying trait.

These features make the brook trout one of the most recognizable and beautiful freshwater fish.

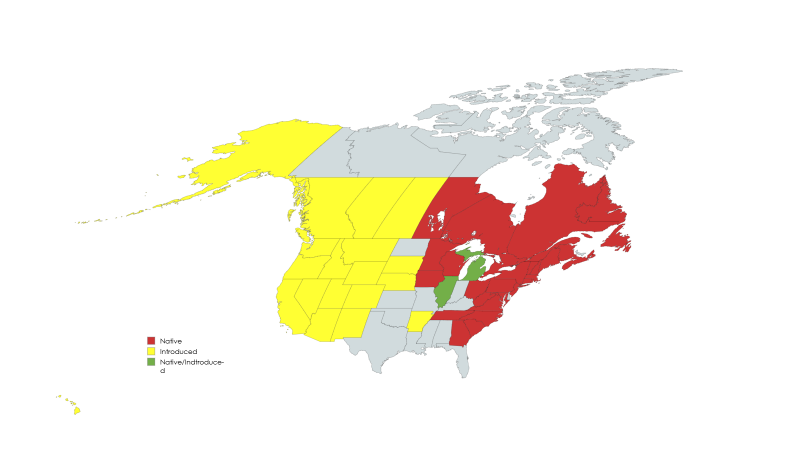

Where Are Brook Trout Found in North America?

Brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) originally inhabited a vast range in eastern North America. Their native habitat spans much of eastern Canada and parts of the United States, following freshwater systems that are cool and clean.

- Northern Range: Their native range begins in Newfoundland and Labrador, extending west to the edge of Hudson Bay and covering large portions of Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba.

- Southern Range: The range stretches down through the Great Lakes and Mississippi River basins to the Appalachian Mountains, reaching as far south as northern Georgia.

- Eastern Range: Brook trout naturally thrive in Atlantic basin waters and streams across the northeastern United States and eastern Canada.

Native Range

The brook trout’s native range includes the following U.S. states and Canadian provinces:

United States:

Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, New York, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Maine, New Hampshire

Canada:

Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Labrador, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba

Challenges in Their Native Range

Unfortunately, brook trout populations have significantly declined across their native range:

- Habitat Loss: Streamside forests have been cleared for development since the late 19th century, leading to sedimentation and the loss of clean, cold-water streams.

- Competition from Non-Native Fish: Introduced species like brown trout and rainbow trout are more aggressive and out-compete brook trout for food and space.

- Pollution and Mining: Appalachian Streams have suffered from acid mine drainage, leaving some areas devoid of fish.

- Fragmentation: Most native brook trout populations now exist only in small, isolated headwater streams.

Introduced Range

Ironically, brook trout have become invasive in some areas outside their native range. In the western United States, they outcompete native cutthroat trout, even contributing to the loss of Lahontan Cutthroat Trout in Lake Tahoe.

Brook trout have been introduced to the following regions:

United States:

Arkansas, Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, Wyoming

Canada:

Labrador, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Quebec,

Brook trout have also been introduced to certain areas outside their native provinces, often with mixed ecological results.

Conservation Efforts

Today, efforts to conserve brook trout focus on restoring habitats, removing invasive species, and protecting the remaining fragmented populations. This ensures that both native ecosystems and the cultural heritage surrounding brook trout can be preserved for future generations.

Ideal Habitat Conditions for Brook Trout

Brook trout do best in cold, well-oxygenated lakes and streams with good water quality. These fish do not tolerate water warmer than 68 degrees Fahrenheit (20 C). Additionally, they need a pH—level in the 5.0 to 7.5 range.

Riverine fish, or the version of these fish that live their entire lives in rivers or streams, will be hanging out beneath undercut banks or near fallen trees or boulders. They need these kinds of features for shelter and also to break the strength of the stream current. Small streams will produce smaller fish that will be a maximum of 10 inches long and live for an average of three years. Larger brookies come from deeper waters of larger rivers, lakes, or saltwater estuaries. Brookies from these better habitats can live up to 6 years and attain much larger sizes.

As mentioned earlier, some of their habitats have problems with acidic mine runoff. Additionally, acid rain, which is caused by coal-burning power plants, factories, and automobiles, is a problem in some of their habitat. While acid rain is still a problem, it was more so in the late twentieth century.

What Do Brook Trout Eat?

Brook trout feed on a wide variety of organisms, including aquatic insects, terrestrial insects, and both aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates. The larger forms of these fish, such as lacustrine and sea-run brook trout, are piscivorous, which feeds on small fish. They’re not picky and are opportunistic feeders. Larger brookies will also feed on the occasional frog or even a small mammal, such as an unlucky mouse.

Coaster Brook Trout

“Coaster brook trout” are mainly potamodromous brook trout from Lake Superior. The term potamodromous refers to freshwater fish that migrate, for instance, to spawn, but they stay in freshwater. Historically there were coaster brook trout in all three of the upper Great Lakes, which consist of lakes Huron, Michigan, and Superior. They were famous for their abundance and their large size. The 14.5-pound world record brook trout was more than likely a coaster. It was caught in 1916 on the Nipigon River, which flows from Lake Nipigon to Lake Superior.

As early as the 1880s, the brook trout population in the great lakes was in severe decline. A big factor in this decline was habitat degradation brought on by man-caused changes to the watershed.

Factors such as logging, road building, and railroad building allowed greater volumes of the spring runoff to run off the land too quickly, carrying with it a heavier load of sediment to clog streams and cover spawning beds. Farm runoff also had a detrimental effect on coaster trout numbers. Today these fish have been expatriated from lakes Huron and Michigan, and although they’ve made somewhat of a comeback, lately, they’re still threatened with expatriation in Lake Superior.

Salter Brook Trout

Salter brook trout or sea-run brook trout are anadromous. Anadromous fish live in saltwater but return to freshwater to spawn. Their historical range in the U.S. once took in most of the Atlantic coastal rivers, streams, and estuaries from Maine down to Chesapeake Bay. Salter trout streams were the first destinations on every sport fisherman’s bucket list due to the numerousness and the size of these fish. In the 1820s, the noted statesman from New Hampshire and Massachusetts, Daniel Webster, reportedly caught a 14 1/2 pound salter brook trout on Long Island in the East Connecticut River (since named Carmans River). This fish wasn’t officially recorded, but it would have tied the current world record for brook trout if it had been.

These fish began to dwindle with the advent of the Industrial Revolution. As streams were dammed or diverted for various purposes, such as mills or cranberry bogs, the fish began to disappear. Today salters are rare below the Gulf of Maine. As you travel north into Canada, you’ll find them to be more abundant. Many of the Rivers and streams that drain into Hudson Bay are home to giant Salter Brook Trout.

Brook Trout Life History

The timing of the spawning season varies somewhat with the geographical area, but in most of their native range, brook trout spawn in October and November. Some brookies spawn in lakes. However, most of the time, their spawning habitat is in rivers and streams. Spawning brook trout seek gravel bars areas with enough current to provide ample oxygenation, such as in rivers, spring-fed streams, or on lake beds with gravel bottoms and upwellings of spring water. Brook trout are also sensitive to temperature. Spawning occurs in water that is between 40 and 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

The female constructs a depression in the gravel called a redd. They use their tails to fan away the gravel, silt, and other materials. Redd is another name for a spawning bed. After constructing her redd, the female will lay up to 5000 eggs. After the male fertilizes them, the female covers the eggs with gravel.

The eggs have to stay free of silt and continuously be washed over by oxygenated water, or they will not survive. It will take 50 to 150 days for the eggs to hatch, depending on the temperature of the water. At this point, the fry still remains in the redd until their yolk sac is absorbed. The vast majority of mortality, whether it be due to predators, disease, or starvation, will occur within the first year of their life. If they make it to the end of their first summer, they will be around four inches long.

Generally, at 2 years of age, they will reach sexual maturity, and it will be the first year that they spawn. They will spawn every year thereafter. If conditions are optimal, they will live for 5 or 6 years.

Conservation Efforts

As I’ve mentioned, brook trout are doing well in some parts of their native range, and in others, they’re struggling or have been completely expatriated.

There are organizations that are restoring brook trout environment and working to restore brook trout to their native range.

Quoted from their website, “the Eastern Brook Trout Joint Venture is a unique partnership between state and federal agencies, regional and local governments, businesses, conservation organizations, academia, scientific societies, and private citizens working toward protecting, restoring, and enhancing brook trout populations and their habitats across their native range.”

Trout unlimited of the U.S and Canada is also very proactive in restoring brook trout to their native range.

Also, look at the Sea-Run Brook Trout Coalition.

- Sea-Run Brook Trout Coalition – Bring Back New England’s Salter Brook Trout! (searunbrookie.org)

- EBTJV (easternbrooktrout.org)

- Trout Unlimited | Home

Recent Posts

The only venomous snakes in Washington State are Northern Pacific Rattlesnakes. The Northern Pacific Rattlesnake (Crotalus oreganus oreganus) is a sub-species of the Western Rattlesnake. Anyone...

Skunks are not classified as true hibernators. But they go into a state of torpor when the weather gets cold. Skunks are light sleep hibernators, along with opossums, bears, and raccoons. ...